Job search pain points: learnings from a small survey.

The survey.

A few weeks ago, we administered an anonymous 2-question survey to 40 students. Our goal was to learn more about the pain points that these students experience in their job search within the US market. The majority of these students are international students enrolled in a STEM Master program who have less than 2 years of work experience in foreign (non-US) markets. Many of these students have no prior work experience at all.

These are the 2 questions that we asked in the survey:

What are the 3 biggest challenges that you are facing in your job search, career progression, or self-development?

What would make you feel more confident in your job search or career progression?

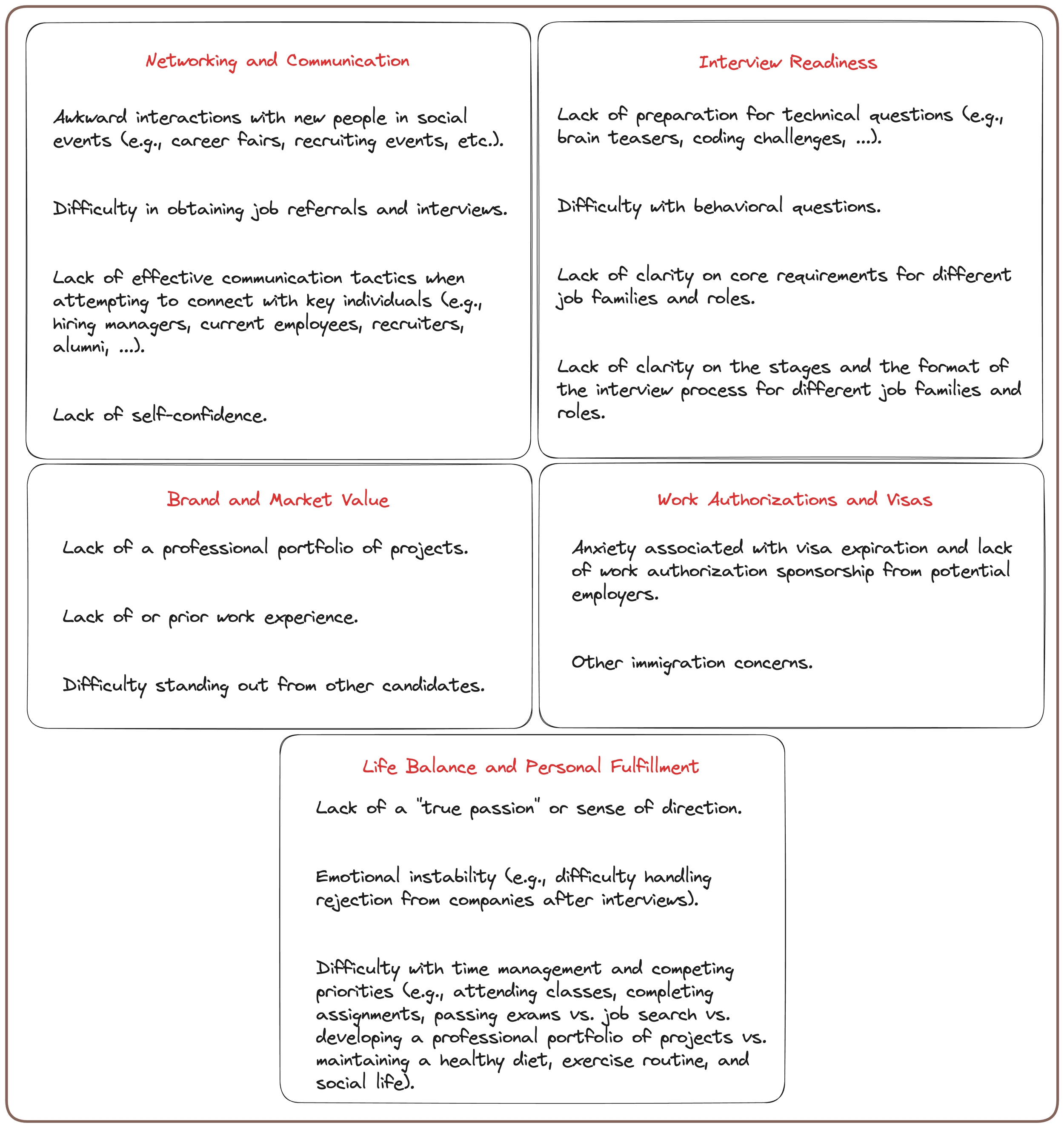

We found 5 recurring themes emerging from their responses:

Networking and communication.

Interview readiness.

Brand and market value.

Work authorizations and visas.

Life balance and personal fulfillment.

After some additional analysis of their responses, we realized that each theme could be further broken down into smaller sub-themes. These sub-themes are summarized in the chart below.

What we learned.

Some of the sub-themes that emerged from the survey responses were not entirely surprising.

For example, we expected to read about the lack of clarity on core requirements for different roles: there is little consensus on the distinctions between different roles, especially for many technical roles in the Data Science domain.

We also expected to find that students are confused about the differences that exist in the stages and in the format of job interviews across different companies, job families, etc. Every employer tends to customize their interview processes on the basis of their own culture, values, and needs. After some exposure to real-world interviews, candidates usually begin to identify common interview patterns within specific groups of employers (e.g. big technology companies vs. consulting firms vs. banks, etc.). But these commonalities are not observable by students and recent graduates who are approaching the US job market for the first time and therefore - by definition - have not been exposed to real-world interviews just yet.

We did expect to read about some students struggling with technical interview sessions (e.g. brain teasers or code challenges): these interview skills are generally not strongly emphasized in the context of traditional academic curricula, often for good reasons. Instead, students tend to discover the existence of this gap only once they begin their interviewing for certain roles. Traditionally, students and recent graduates have been put in a position in which they have to quickly develop these skills autonomously through a good amount of deliberate practice.

Difficulties with work authorizations and visas are another concern that we expected to encounter. Especially during economic downturns, employers can become more reluctant to sponsor H1B visa applications. Often, the same reluctancy also extends to temporary employment options such as the Optional Practical Training (OPT) work authorization that is generally granted under the F1 student visa.

On the other hand, some of the sub-themes that emerged from the survey were not entirely obvious.

In particular, we were surprised about the fact that some of the students lamented not having found a “true passion” in life. Others indicated self-confidence problems and difficulties with managing their time. In general, we find that international students are among the brightest, most motivated, most organized, and most resilient students. We can’t help but wonder whether the difficult job market conditions that they are currently facing are correlated with their sentiments of struggle and lost sense of direction.

Another interesting element that surprised us is the difficulty that some students find in interacting with newly met people in the context of social settings (e.g. career fairs or other recruiting events). Cultural differences are most likely the key contributor to this lack of ease, but we wonder whether self-induced anxiety may be another underlying cause: for these students, a lot is at stake in every interaction with an individual who can make or influence hiring decisions.

Solutions.

Our simple survey has obvious limitations. It only covers a very small group of students (40) within a specific segment (pre-experience, international, STEM students), in the context of a specific STEM Master program offered by a specific school in a specific university. Despite its limitations, the survey still provides relevant partial information about how a certain segment of pre-experience international students feels about their job search.

In our opinion, most of the challenges that these students face can be significantly reduced with appropriate coaching. For example, we can:

Create frameworks to help them conceptualize some high-level taxonomies of job families and roles.

Educate them about the key differences that exist between job interviews at e.g. consulting firms vs. tech companies vs. other types of companies.

Coach them on strategies that allow them to represent their best selves in behavioral interviews.

Provide opportunities to develop the minimal required level of competency for brain teasers, coding challenges, and other types of technical interviews.

Visa and work authorization issues are a complex topic, but coaching services like ours can connect students and recent graduates with trusted immigration attorneys. Very often, these attorneys can propose viable alternatives to the OPT work authorization or the H1B visa lottery for international students, and they can help implement these alternatives earlier on (rather than close to graduation or after).

For personal growth and development, there is no substitute to personalized coaching and mentorship. In particular, a personalized plan is key to helping students strengthen their self-confidence, sense of purpose, and resilience. We expose our students to a premium network of industry professionals. This network provides a safe, relaxed, low-stakes environment in which they can build lasting professional relationships and get faster access to relevant job opportunities. By interacting with our network, our students also see rapid improvements in their understanding of the US work culture and in their ability to adapt to it.

While there is no silver bullet to guarantee employment for recent graduates, we are confident that coaching is a very effective way to stack the odds in their favor.